Meta.Morf 2022 / Cinemateket Trondheim / Screenings June 17 / Curator: Jeremy Welsh

Tickets NOK 90 / 120.

SCREENS revived and revisited, 1997 – 2022

Inger Lise Hansen / Jeremy Welsh / Kaia Hugin / Lene Grenager / Michael Francis Duch / Piya Wanthiang / Tijs Ham / Vibeke Jensen / Øyvind Brandtsegg

An illustrated talk, screening and concert at Trondheim Cinematek to celebrate the 25th anniversary of electronic arts festival Screens, the forerunner of Meta.Morf.

The screening programme will feature old and new film/video works, including Ivar Smedstad’s work Centuryfuge 255, one of the video works featured in the Screens exhibition, 1997. From the same exhibition, artist/architect Vibeke Jensen will be represented in a video interview recorded in the early 2000’s. There will be a film by Inger Lise Hansen, a Trondheim native, and an internationally renowned experimental film maker. Documentation of the ’97 Screens exhibition will also be presented.

Of more recent works, the programme will include Flyttestein by film/video artist Kaia Hugin, a work originally commissioned for a show at Rake Visningsrom, Trondheim, in 2016. Also shown will be Uns-table, a short sound-image work made by composer Øyvind Brandtsegg together with electronic musician Tijs Ham, visual artist Piya Wanthiang and videomaker Jeremy Welsh.

The programme includes a live concert, Reconstruction V, a work for recorded sound, digital film and live contrabass, composed by Lene Grenager and performed by Michael Francis Duch with projections by Jeremy Welsh. The work was premiered in January 2022 at Inderøy Kulturhus and Dokkhuset, Trondheim, later performed at Café Hærverk in Oslo. Grenager and Duch are both members of leading contemporary music ensemble Lemur and have often collaborated with visual artists and film makers.

The duration of the programme will be approximately 90 minutes.

The Screens Website

From Screens 1997 to Meta.Morf 2022. (25 years of art and technology in Norway)

Jeremy Welsh, 2022

In 1997 the city of Trondheim marked its 1000th. anniversary and to celebrate this historic occasion the municipality initiated a substantial programme of cultural activities. One such event was Screens, a major festival of electronic and digital art, taking place at several venues across the city during the month of October. The background to this festival lay several years earlier in the establishment of the Intermedia Department at Trondheim Academy of Art and the city of Trondheim’s positioning of itself as Norway’s primary centre for research and development in new technologies. The year before Screens, 1996, saw the establishment of NTNU, the Norwegian University for Science and Technology. The art academy was incorporated into the new university, within the faculty of architecture (AD fakultetet). An interest in culture and new technology had been steadily growing in Norway throughout the nineteen nineties, and a number of other significant cultural manifestations had already taken place, including Electra at Henie Onstad Kunstsenter in Bærum and the Cyberconf, the sixth international conference on cyberculture, held at the University of Oslo in June 1997 with an exhibition at Kunstnernes Hus in Oslo. Earlier in the decade (1993) the printmaking workshop Atelier Nord in Oslo established facilities for video editing and computer graphics, starting the organization’s transition to become Norway’s first artists’ media centre.

Screens was developed in response to a challenge from the cultural section of Trondheim municipality to arrange an event celebrating the city’s profile as a centre for research and development within new technologies and the arts. Jeremy Welsh and Espen Gangvik were co-curators and producers of the festival, which was supported by the city, by Arts Council Norway, The Nordic Council of Ministers and the EU. International partners included Färgfabriken, centre for art and architecture in Stockholm and The Film and Video Umbrella (FVU), a curatorial and production agency for artists’ film and video in London. The main site of the programme was Trondheim Kunstmuseum, which housed a series of video works and interactive digital installations, as well as sculptural works created through digital technologies. Close by, at the Archbishop’s palace of Nidarosdomen (Trondheim Cathedral) “The Messenger” a major work of US artist Bill Viola was staged in a medieval chapel., while at the same time his earlier work “Anthem” was shown at the museum. This was the first significant presentation in Norway of the work of Viola, one of the most established names in international video art.

Elsewhere in the city, screenings, seminars, performances and a conference were staged at venues including Lademoen Artists’ Centre and Trondheim Cinematheque. A survey exhibition of work by students emerging from the art academy’s Intermedia Department was shown at the Academy’s own space, Galleri KiT.

Several new works for the exhibition were commissioned by Screens, while others were restaged, including the Viola installation that had first been exhibited at Durham Cathedral in England. Parts of the programme were co-curated by partners Jan Åman (Färgfabriken) and Steven Bode (FVU). The seminar programme brought together significant speakers from fields including media theory, media archeology, architecture and digital art. A special edition of the art academy newspaper Kitsch functioned as catalogue for the festival, and was accompanied by a CD Rom that included specially made digital works by artists commissioned for Screens.

The Screens publication featured texts by a number of leading theoreticians within art and new media, including Lev Manovich, whose subsequent book The Language of New Media became one of the key reference books of the early 21st century. For the Screens catalogue Lev Manovich contributed a text entitled Archeology of a Computer Screen, a theme he developed further in a lecture at the Screens conference. He traces the development of the screen as window/interface to another space or reality from Renaissance painting, through photography and film, to contemporary VR and digital screen culture. While describing the historical progressions of the screen format he also differentiates between the origins and evolutions of different technologies:

“The origins of the cinema’s screen are well known. We can trace its emergence to the popular spectacles and entertainment of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: magic lantern shows, phantasmagoria, eidophusikon, panorama, diorama, zoopraxiscope shows, and so on. The public was ready for cinema and when it finally appeared it was a huge public event. Not by accident the ”invention” of cinema was claimed by at least a dozen individuals from a half dozen countries.

The origin of the computer screen is a different story. It appears in the middle of the century but it does not become a public presence until much later; and its history has not yet been written. Both of these facts are related to the context in which it emerged; as with all other elements of modern human-computer interface, the computer screen was developed by the military. Its history has to do not with public entertainment but with military surveillance.”

In the 25 years since the Screens festival, the ubiquity of screens and related technologies has complicated the story proposed by Lev Manovich in his prescient text. By now there are many histories of computer technologies and the field of media archeology is well established, whilst the role of the screen as an instrument of surveillance has transcended its military genesis to deliver us to the culture of global surveillance capitalism.

Another leading theorist of digital technologies and media archeology is Finnish academic Erkki Huhtamo, now a professor at UCLA. Huhtamo contributed a lecture on media archeology to the Screens conference, performed “remotely” as a pre-recorded guide to his “museum of media archeology” – a large collection of pre-digital display technologies.

During Meta.Morf 2022, the legacy of Screens will be celebrated in a talk, screening and concert at Trondheim Cinematek on Friday 17th. June. The screening programme will include works from the original Screens exhibition, such as Ivar Smedstad’s video Centuryfuge 255, a work that is equally relevant today in its imagery of industrial machinery manipulated digitally through morphing software. As much a reiteration of tropes of early avantgarde cinema as an exploration of digital image processing, it is a work that sits at the cusp of the analog/digital divide in moving image culture and reads as a document of post-industrial culture. Also included in the programme will be a live cinema event that is a collaboration between composer Lene Greenager, musician Michael Francis Duch and video artist Jeremy Welsh. Like Ivar Smedstad’s video from the mid nineties, this is a work that takes the heritage of industrial production as a starting point. Lene Grenager made sound and video recordings of machinery from the textile industry and then developed a composition based on sound samples from these recordings. A score for live double bass was added to the base track of machine sounds, and then a digital film was made using the video recordings, combined with still photographs from similar post-industrial environments. The resulting work is a 28 minute performance featuring digital video projection, electronic sound and live contrabass. The work was first performed in January 2022 at Inderøy Kulturhus and Dokkhuset, Trondheim.

The Screens exhibition and festival in itself was one of the largest manifestations of art and new technology to take place in Scandinavia during the nineties, but one of its most important legacies arose from a special meeting held at Lademoen Kunstnerverksted with representatives from the visual arts department of the Norwegian Arts Council. A consequence of this meeting was that a working group was established to look into the production opportunities for electronic arts in Norway and to produce a report with recommendations for what might be done to consolidate the field. The working group was established in 1998 under the leadership of artist Synnøve Persen, a member of the board of the Norwegian Arts Council. Other members were artists representing the field of electronic arts; Kenneth Korstad Langås and Kristin Bergaust, both from Atelier Nord; sound artist Siri Austeen, and Jeremy Welsh, professor of Intermedia at KiT/NTNU. The group’s secretary was Anne Wiland, who authored the document SKJØNNHETEN OG UTSTYRET, produksjonsnettverk for elektronisk basert billedkunst, arbeidsnotat nr. 31. The document was based on a series of meetings held by the working group during 1998, and a study trip to Germany and The Netherlands, where several media arts centres were visited in order to collate information about the various models and organization structures that were in place.

The recommendation of the working group was the establishment of new media centres in Oslo, Trondheim and Bergen, and a national network, the Production Network for Electronic Arts (PNEK) to be based on these three centres in addition to NOTAM, the Norwegian Centre for Technology, Art & Music in Oslo. Atelier Nord was already established as an Oslo node, while BEK (Bergen Centre for Electronic Arts) was soon to be founded, and in Trondheim, Top Floor, a digital arts workshop at Lademoen Kunstnersenter was initiated, and formed the basis for what subsequently became TEKS, Trondheim Electronic Arts Centre in 2002.

A further consequence of the process initiated at the Trondheim meeting in 1997 was the creation of a specific funding initiative for Art and New Technology within the visual arts department at Arts Council Norway. This became formalised in the autumn of 2001, with its own specialist committee, led by Jeremy Welsh. For the first time in Norway, a funding structure existed with the specific mandate to support and stimulate developments within art and technology. For almost two decades, numerous experimental art and technology projects were made possible through the support of this fund.

PNEK, the Production Network for Electronic Arts, was also established in 2000, with a national coordinator based at Atelier Nord in Oslo. BEK had been started in Bergen, partly as a result of projects developed for Bergen as European City of Culture in 2000. The initial intention for PNEK was that it should stimulate and co-ordinate collaborative activities between the various nodes. The first collective effort was the workshop/performance/exhibition The Living Room, arranged in Trondheim in the autumn of 2001 with participants from TEKS, BEK, Atelier Nord and NOTAM. A five day production workshop was held in Galleri KiT, the art academy’s exhibition space, with a public exhibition and performance at the end of the week. The event was interdisciplinary and experimental in nature and had much in common with other productions that mixed the disciplines of visual art, electronic music and performing arts. For example, the workshop Hot Wired Live Art in Bergen in 2000, which included performance group Motherboard (Per Platou, Amanda Steggel, Ulf Knudsen). Motherboard had already established a reputation as innovators within dance and the performing arts through performances at the Electra exhibition at Henie Onstad Kunstsenter and Kunstnernes Hus in Oslo. They pioneered the use of live, internet-based video in performance, using the early technology CUCme, and one of their collaborators was Canadian artist Michelle Teran, who would later become an artistic researcher in Bergen and then an associate professor at Trondheim Academy of Art. Another significant group within the live arts was Verdensteatret, whose complex stage shows combined live performance, robotics, video projection and digital sound. In Bergen the performance group Baktruppen were also innovators in the field of live arts. BiT teatergarasjen, Bergen’s stage for experimental performance practices, has been an important meeting point for artists from a broad range of backgrounds, and as part of a national network that includes Teaterhuset Avant Garden (Rosendal Teater) in Trondheim and Black Box in Oslo, has provided an outlet for art and technology projects that are geared towards theatrical presentation rather than exhibition.

Over ensuing years the PNEK network expanded to take in new nodes including i/o Lab in Stavanger, Atopia in Oslo, Lydgalleriet (The Sound Gallery) and Piksel festival in Bergen. Support for the network was withdrawn in 2018 and it was formally dissolved in 2021, though several of the nodes are still in operation and continue to publicize their activities through new network collaborations. The earmarked funding for Art and New Technology was terminated in 2018 and subsequently art and technology projects were expected to apply alongside all other cultural activities to the various funding streams within the Arts Council. Funding was also cut for i/o Lab and Atopia, two of the longer running projects within the PNEK system. i/o Lab had developed a strong focus on bio art and arranged several festivals or exhibitions highlighting this field. Atopia had started out as an informal screening room and meeting place for film and video artists, and went on to develop the public screening project Vitrine, using the gallery’s large street-level display windows. Atopia’s artistic director Farhad Kalantary also curated Retrospective, a major survey of artists’ film and video in Norway from 1960 to 1990, staged at Stenersens Museum in Oslo.

Trondheim’s status as one of the Nordic region’s most important nodes for digital art has been carried forward by TEKS through several programmes and initiatives. Between 2002 – 2010 TEKS arranged the annual festival Trondheim Matchmaking, a meeting place for artists and technologists, aimed at creating platforms for collaboration. The project was terminated after 2009 and superseded by Meta.Morf which began in 2010 as an international biennale of art and technology, presenting an ambitious programme of exhibitions, performances, conferences and seminars at multiple venues in the city of Trondheim.

Each edition of Meta.Morf has had a particular theme and focus, thus allowing it to concentrate more specifically on a given curatorial concept, rather than functioning as a survey or showcase such as Ars Electronica. A brief look at the subtitles of the seven editions of Meta.Morf to date illustrates the range of themes, topics and issues that have been highlighted in the biennale’s programmes. New.Brave.World in 2010; A Matter of Feeling in 2012; Lost in Transition, 2014; Nice to be in Orbit!, 2016; A Beautiful Accident, 2018; The Digital Wild, 2020 and Ecophilia, 2022. Since 2018 TEKS.studio has been in operation as a gallery and event space, presenting solo exhibitions by artists working with technology, and organizing workshops and seminars. A publishing platform. TEKS.press, has also been established, building upon the series of Meta.Morf publications that have followed the biennale. The most recent publishing project is “Elektronisk Kunst i Norge” (Electronic Art in Norway) a compendium of artist profiles covering the period from 1960 to the present, and edited by Zane Cerpina, Ståle Stenslie and Jøran Rudi.

In 2022 Notam, BEK, Lydgalleriet, Atelier Nord, Piksel and TEKS are all still active with varied programmes including exhibitions, workshops, production, seminars and festivals. 2022 sees the latest edition of Meta.Morf, back in public spaces in Trondheim, Namsos and Inderøy after the 2020 edition had been suddenly suspended due to Covid restrictions, which came into force only days after the opening March 5. Though most of the postponed programme eventually was presented during the autumn of 2020, the 2022 edition will be the first full-scale event since 2018. The 25 years that separate Screens from Meta.Morf 2022 have seen many developments within the art and technology field, a broadening of the technologies and practices with which artists engage, a limited incursion into the mainstream of contemporary art, and the rise and fall of certain genres. For example, net.art had its heyday in the 1990’s and early 2000’s when artists, activists and hackers took to the internet as an arena with great potential. The subsequent corporatisation of the world wide web and the ubiquity of commercial online services eroded the possibilities, while technological developments quickly rendered many experimental net-based projects obsolete. The recent surge of interest in NFT art perhaps indicates a new era of internet-based art, but what has been seen so far does not indicate the kind of radical, critical approach that was characteristic of earlier net art, but rather an opportunistic engagement with online finance and crypto currencies. Coming years will show whether this new form will mature to become an important area of art practice, or if it will turn out to be another in a history of short lived phenomena within digital culture.

Concurrent with the ongoing expansion of electronic, digital and other technological art practices, the field of digital humanities and the connected practices of digital literature have also undergone a major development over the past two decades. Within the Norwegian context the University of Bergen has been the primus motor for developments in this field, through the work of Scott Rettberg, Jill Walker Rettberg and colleagues at the institute for digital culture within the faculty of Linguistics, Literary and Aesthetic Studies. Their multi-disciplinary research has embraced a range of practices including digital poetry and fiction; non-linear film, game development, VR and digital art. At the University of Oslo, research has focussed on media archeology and histories of the moving image in relation to visual art, while at Oslo Met, digital artist Kristin Bergaust, one of the initiators of PNEK, has developed a research project that encompasses VR technologies, bio art and augmented reality technologies. At NTNU in Trondheim the institute for music technology, under the leadership of composer Øyvind Brandtsegg, is currently the environment that focuses most on developments in technological art practice, while the department of Fine Art no longer has a clear commitment to art and technology developments. An inter-faculty network for art and technology within NTNU, although a promising initiative, failed to deliver the standard of artistic projects that could have been expected. It could also be claimed that by not forging a close relationship with Meta.Morf as a logical “shop window” for research in art and technology in Trondheim, NTNU missed an opportunity that could have enhanced its international standing as an innovative university.

In 2022 the new National Museum will open in Oslo, and with the exception of showing a few film/video works, there is so far no indication that the museum has ambitions to develop any major innovations in the exhibition of technological art. The national Video Art Archive, developed through PNEK and Atelier Nord between 2011- 2020, is now localized within the library and archive department of the museum, but so far there is no indication that the museum intends to actively promote this digital collection. Major public exhibition spaces that show some commitment to presenting technological art include Kunstnernes Hus, Henie Onstad art centre and Bergen Kunsthall, and in all cases, the art and technology component of overall exhibition programmes is somewhat limited. Many contemporary exhibitions inevitably include some proportion of electronic or digital art, and it is indisputable that video and film are a central part of the contemporary mainstream. However, the more experimental, technologically challenging and aesthetically radical aspects of technological art are mostly absent from the programmes of major museums and galleries.

While the uptake of art and technology projects within the museum and gallery sector has been slow, several festivals have been more pro-active, in particular the contemporary music festivals Ultima in Oslo and Borealis in Bergen. New Music Norway’s annual Only Connect festival has also provided an arena for electronic music and digital sound art, while Punkt festival in Kristiansand, led by composer and musician Jan Bang, has a particular niche and a clear profile within contemporary electronic music. Piksel in Bergen, led by artist Gisle Frøysland, has developed a clear focus on the links between art, technology and activism in its profiling of open source software and hardware and related strategies of repurposing, reusing or recycling technologies within an experimental framework. Norway currently has three gallery spaces that are dedicated to the exhibition of technological art projects; TEKS.studio, Atelier Nord and Lydgalleriet. All of these operate with limited budgets and require a high level of dedication from small production teams to deliver ambitious exhibition projects.

Meta.Morf 2022 opens at a moment when the whole cultural sector in Norway and beyond is emerging from a two year hiatus caused by the Corona pandemic. How large international festivals and biennales will operate in the future is so far unknown. Also unknown is how the termination of PNEK and the abolition of the fund for art and new technology will impact technological art practices in Norway in the near future. It is something of a paradox that in an era when society’s dependence upon networked technology has been so clearly emphasized, that there is a lack of commitment from public funding bodies and educational establishments to actively and ambitiously build a culture of critical and creative technological art practices. Although it is true that younger generations have grown up with technology and have a different kind of digital literacy, this in itself is not enough to build a sustainable field of professional practice – any more that the ability to hold a pencil would have guaranteed that previous generations might become great painters.

With its material wealth, its particular demographics, an increasingly international and multi-cultural society, a high average level of education and a nation-wide network of cultural institutions, Norway is well-positioned to become a leading international actor within contemporary culture, which logically, must encompass a high level of engagement with new technologies and a commitment to support and develop experimental and innovative artistic practices across all branches of culture. This requires a reassessment of current funding strategies at national and local levels as well as a broadening of the understanding of contemporary art practices within the major exhibiting institutions. The role of Meta.Morf will, in short, continue to be crucial in raising awareness of the fields of technological art, while the remaining nodes of the PNEK network will continue to be the basis for the ongoing development of art and technology projects within Norway.

Further reading:

Elektronisk Kunst i Norge, bind I: Kunstnere og verk fra 1960 til 2020. Eds. Zane Cerpina, Jøran Rudi, Ståle Stenslie. TEKS.press, 2021.

Around Which Dissonant Satellites Cluster: 20 år med Bergen senter for elektronisk kunst. Eds. Vilde Salhus Røed, Maria Rusinovskaya. BEK, 2022.

PARADOKS: posisjoner innen norsk videokunst 1980 – 2010. Eds. Eva Klerck Gange, Birgitte Sauge, Marianne Yvenes. Nasjonalmuseet / Museet for samtidskunst, 2013.

Tech-Stiles. Eds. Charis Gullickson, Morten Johan Svendsen, Knut Ljøgodt, Hilde Hauan Johnsen. Sogn & Fjordane Kunstmuseum, 2012.

Maleri med Tid: Om modernisme, filmisk avantgarde og videokunst. Per Kvist. Novus Forlag, 2013.

Lives and Videotapes: The Inconsistent History of Norwegian Video Art. Marit Paasche. Feil Forlag / Videokunstarkiv, 2014.

Retrospektiv: film- og videokunst i Norge, 1960 – 90. Eds. Farhad Kalantary, Linn Lervik. Atopia Stiftelse, 2011.

Eksenter (Hvor finner kunst sted). Leiken Vik & Solveig Lønmo. Forlaget Press, 2016.

Elektrisk Lyd i Norge fra 1930 til 2005. Jøran Rudi. Novus Forlag, 2019.

Remediating the social: Electronic literature as a model of creativity and innovation in practice. Ed. Simon Biggs. University of Bergen, Dept. of Linguistic, Literary & Aesthetic Studies, 2013.

Header Graphics: “Flyttestein” by Kaia Hugin.

Eirik Havnes er en poet, musiker, komponist og lydkunstner fra Ålesund som de siste årene har jobbet med natur som et gjennomgående tema innen alle sine kunstretninger.

Eirik Havnes er en poet, musiker, komponist og lydkunstner fra Ålesund som de siste årene har jobbet med natur som et gjennomgående tema innen alle sine kunstretninger.

Stavanger-born vocalist, performer and sound artist Stine Janvin works with the extensive flexibility of her voice, and the ways in which it can be used to channel physicality of sound. Created for variable spaces from theatres, to clubs and galleries, and more recently websites and digital platforms, the backbone of Janvin’s projects focus on exploring performance formats, vocal instrumentation and potential dualities of the natural versus artificial, tangible/digital, and minimal/dramatic.

Stavanger-born vocalist, performer and sound artist Stine Janvin works with the extensive flexibility of her voice, and the ways in which it can be used to channel physicality of sound. Created for variable spaces from theatres, to clubs and galleries, and more recently websites and digital platforms, the backbone of Janvin’s projects focus on exploring performance formats, vocal instrumentation and potential dualities of the natural versus artificial, tangible/digital, and minimal/dramatic.

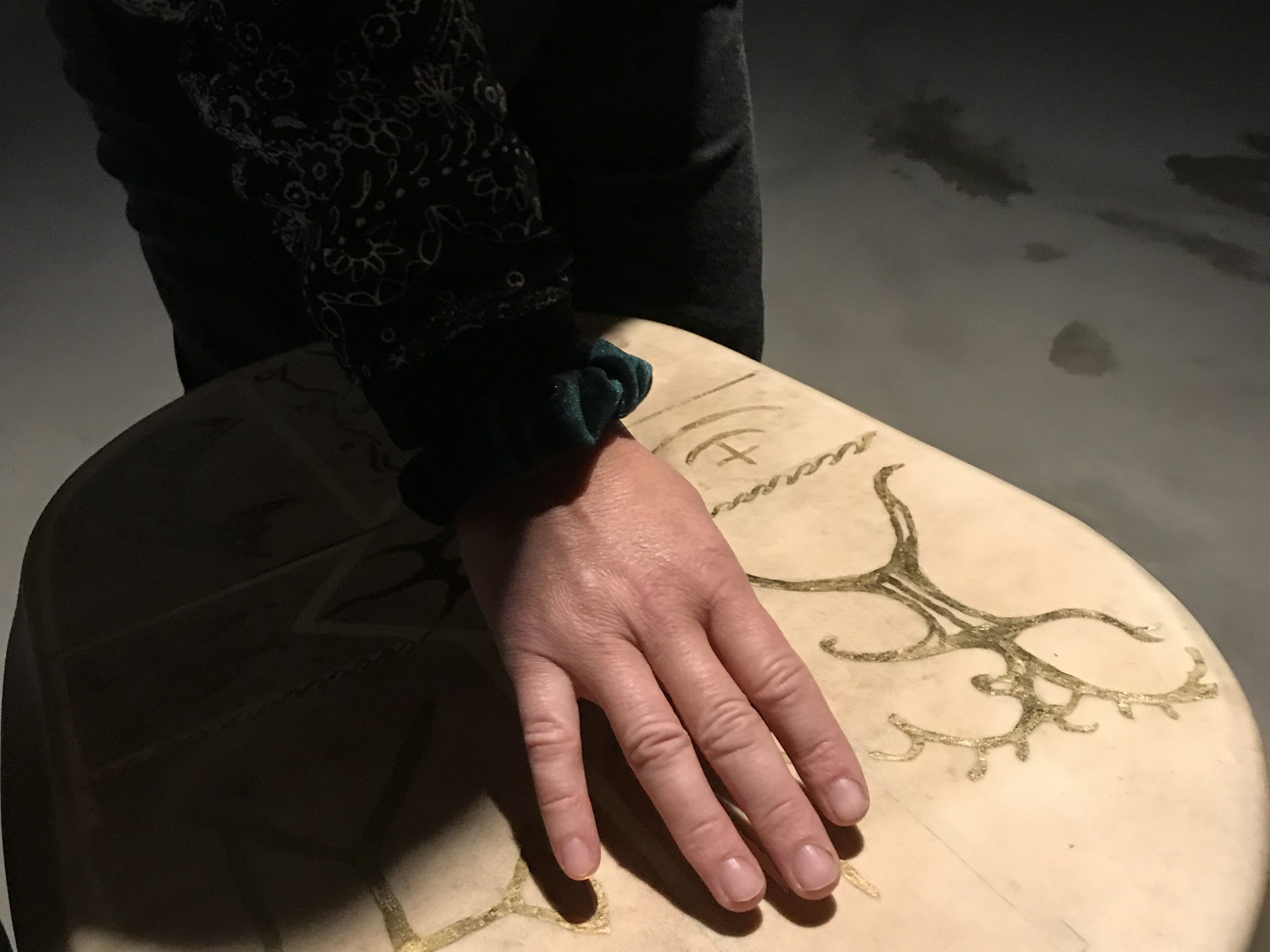

Vassvik is the crew around mastermind Torgeir Vassvik. The Sami musician, Joik artist and composer was born and raised in Gamvik, Sápmi/Norway and now lives mainly in Oslo. His first and main instrument is the voice in all its facets, based on the Sami Joik. He grew up with the mandolin music of his father, trained himself on the guitar, played in indie rock bands, uses prepared guitars, bass, munnharpe, flutes, horns and the Sami frame drum.

Vassvik is the crew around mastermind Torgeir Vassvik. The Sami musician, Joik artist and composer was born and raised in Gamvik, Sápmi/Norway and now lives mainly in Oslo. His first and main instrument is the voice in all its facets, based on the Sami Joik. He grew up with the mandolin music of his father, trained himself on the guitar, played in indie rock bands, uses prepared guitars, bass, munnharpe, flutes, horns and the Sami frame drum. Stahl Stenslie is an artist, curator and researcher, specializing in experimental art, embodied experiences and disruptive technologies. His research and practice focus on the art of the recently possible – such as panhaptic communication, somatic sound and holophonic soundspaces, and disruptive design for emerging technologies. In 1993 he built the cyberSM experiment, the first tactile, cybersex communication system in the world. He has been exhibiting and lecturing at major international events (ISEA, DEAF, Ars Electronica, SIGGRAPH) and moderated symposiums like Ars Electronica (Next Sex), ArcArt and Oslo Lux. He represented Norway at the first Ichihara Biennial, Japan, the 5th biennial in Istanbul, Turkey, co-organized 6cyberconf and won the Grand Prize of the Norwegian Arts Council. As a publisher he is the editor of EE – Experimental Emerging Art magazine (eejournal.no), he has written numerous scientific articles and co-founded The Journal of Somaesthetics (somaesthetics.aau.dk). His PhD on Touch and Technologies (virtualtouch.wordpress.com).

Stahl Stenslie is an artist, curator and researcher, specializing in experimental art, embodied experiences and disruptive technologies. His research and practice focus on the art of the recently possible – such as panhaptic communication, somatic sound and holophonic soundspaces, and disruptive design for emerging technologies. In 1993 he built the cyberSM experiment, the first tactile, cybersex communication system in the world. He has been exhibiting and lecturing at major international events (ISEA, DEAF, Ars Electronica, SIGGRAPH) and moderated symposiums like Ars Electronica (Next Sex), ArcArt and Oslo Lux. He represented Norway at the first Ichihara Biennial, Japan, the 5th biennial in Istanbul, Turkey, co-organized 6cyberconf and won the Grand Prize of the Norwegian Arts Council. As a publisher he is the editor of EE – Experimental Emerging Art magazine (eejournal.no), he has written numerous scientific articles and co-founded The Journal of Somaesthetics (somaesthetics.aau.dk). His PhD on Touch and Technologies (virtualtouch.wordpress.com).