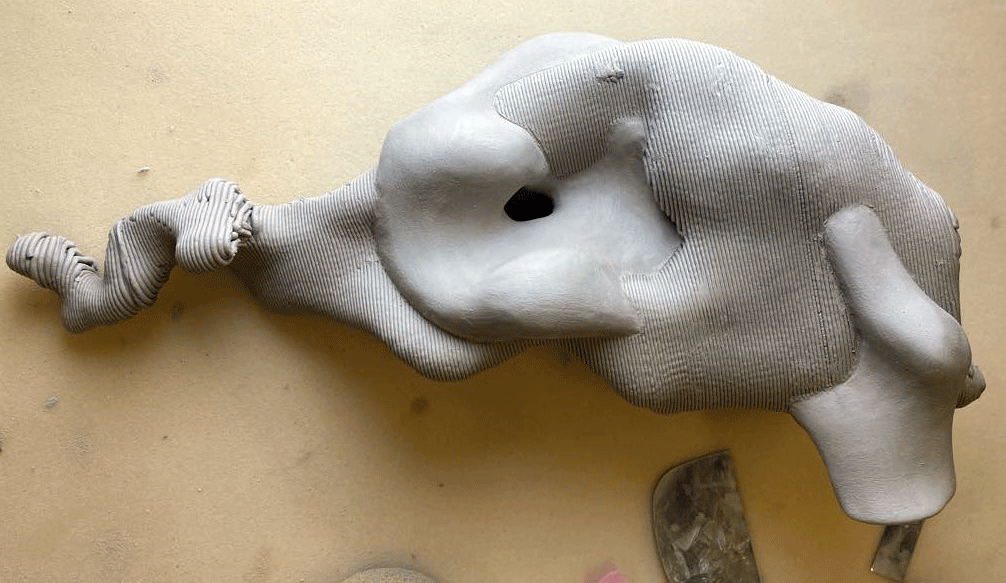

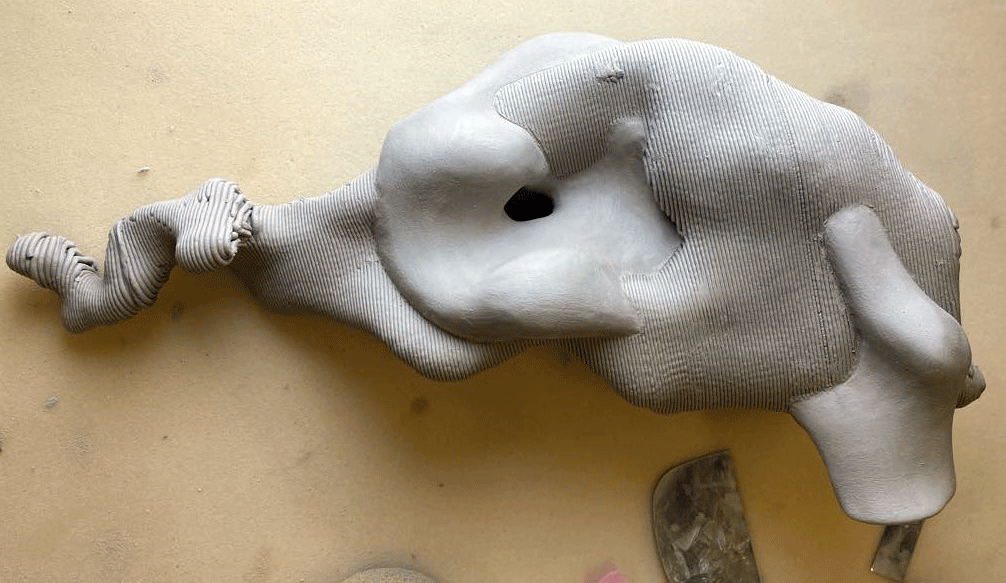

Reconstructing Olympia (2023) / Helene Skuterud

3D-printed Ceramic in white stoneware clay with porcelain terra sigillata and birch ash. Fired to 1240 °C in a reduction atmosphere.

“Reconstructing Olympia” springs from the piece “Deconstructing Olympia” created in 2022, which I hand-built in clay, layer by layer, using a traditional coil-building technique. The sculpture draws inspiration from the classical posture of reclining women in art, “Venus Pudica,” and Edward Manet’s painting “Olympia” (1863). Unfortunately, this sculpture broke in two during the firing process. The two pieces were 3D-scanned and digitally manipulated before rematerializing in clay through the 3D printer. “Reconstructing Olympia” is part of my ongoing project, which involves exploring a 3D-scanned form through digital manipulation and 3D printing in clay. One can distinguish the original sculpture’s two pieces by their surface texture: one is smoothed out, and the other retains the distinctive coiled pattern from the 3D printer.

A 3D printer functions as an automated coil maker, duplicating my actions with much greater precision than I can accomplish myself. While I program the machine, it also exerts its influence on the process, effectively becoming a collaborator. In this struggle, we emerge as equal participants in the creative process, with me becoming inseparably intertwined with both the 3D printer and the clay.

In my work, I explore questions about how 3D technology and hardware become new focal points alongside the material and myself as an artist and how this influences my artistic expression. What occurs when there is suddenly a computer, digital technologies, and a multitude of metal and mechanics between the clay and me? Can we still love each other? Do I lose the emotional aspect in the machine’s interpretation? My form is digitalized, analyzed, processed, and then built up layer by layer, replacing the smooth surface with contour lines that form a topographical description of the sculpture’s terrain. For every loss, there is also a gain of something else that invites new interpretations.

Posthumanism challenges the anthropocentric mindset and redefines what it means to be “human” in a world where technology and nature are inseparably intertwined. It does not perceive humans as isolated entities but rather as integral parts of a larger ecosystem that includes technologies, animals, plants, and machines. Both biological and technological entities can be considered equal participants in a posthuman world. 3D printing in clay exemplifies how technology and nature can come together. The technology and machine are utilized to shape a natural resource. From a posthumanist perspective, one can regard the 3D printer as a non-human actor of equal importance to me, the user. Given that the 3D printer plays a vital role in the process, it can also be seen as a subject, parallel to myself as an artist.

For me, 3D technology has unlocked new avenues for exploring form and materiality. Integrating technology into ceramic sculpture enables me to delve into questions of identity, consciousness, and the human experience in a world where technology assumes an increasingly significant role. It influences our perception of ourselves and our connection to the surrounding world, ultimately shaping our understanding of what it means to be human.

Artistic practice is an eternal journey of exploring ideas, concepts, and techniques. Challenging myself to not always seek completion, but instead to remain in the method and repeat the same process multiple times has resulted in significant learning. Repetition introduces variation in both the process and the results. Having a digital sculptural form in contrast to a finished fired ceramic object grants me the ability to revisit and adjust. This ensures that the process remains ongoing, and the 3D print captures a momentary snapshot of the progress rather than representing a finished object.

Helene Skuterud (NO) resides and works in Oslo. She is presently pursuing studies in material-based art at the Oslo National Academy of the Arts. Previously, Skuterud earned a bachelor’s degree in Three-Dimensional Design from the Birmingham Institute of Art and Design and a Master’s degree in Lighting Design from Sydney University. In recent years, she has served as a designer/maker for Lysrommet. Skuterud’s primary medium is sculpture and clay. She molds organic and abstract forms, ranging in size from handheld pieces to larger objects. These sculptures are either hand-built using coiling techniques or assembled from handcrafted and cast elements. Additionally, she delves into 3D technology, providing her with new avenues to explore form and materiality. Through incorporating technology into ceramic sculpture, she explores questions about identity, consciousness, and human experience in a world where technology holds an increasingly prominent role. Using clay, Skuterud strives to convey something about our surroundings and the bodies we inhabit. She seeks something familiar in the clay, aiming to engage the senses and consciousness through this material.

Helene Skuterud (NO) resides and works in Oslo. She is presently pursuing studies in material-based art at the Oslo National Academy of the Arts. Previously, Skuterud earned a bachelor’s degree in Three-Dimensional Design from the Birmingham Institute of Art and Design and a Master’s degree in Lighting Design from Sydney University. In recent years, she has served as a designer/maker for Lysrommet. Skuterud’s primary medium is sculpture and clay. She molds organic and abstract forms, ranging in size from handheld pieces to larger objects. These sculptures are either hand-built using coiling techniques or assembled from handcrafted and cast elements. Additionally, she delves into 3D technology, providing her with new avenues to explore form and materiality. Through incorporating technology into ceramic sculpture, she explores questions about identity, consciousness, and human experience in a world where technology holds an increasingly prominent role. Using clay, Skuterud strives to convey something about our surroundings and the bodies we inhabit. She seeks something familiar in the clay, aiming to engage the senses and consciousness through this material.

instagram.com/helene.skuterud

Yanina Zaichanka (BY) is a Belarusian artist who is currently studying at the Oslo National Academy of the Arts. Prior to moving to Oslo, she had been actively involved in the contemporary art scene in Minsk. In 2018-2019, she studied Contemporary Art and Drama at the European College of Liberal Arts in Belarus. Her work has been shown at several solo exhibitions, including Untitled at the gallery Seilduken 2 in Oslo (2023), the Freedom (of Speech) from the Unbearable at Pradmova Festival of Intellectual Literature in Minsk (2020), and Being a Woman at ECLAB in Minsk (2019). Zaichanka has contributed to group shows, among others – Solarpunk Festival Exhibition at Kinogalleriet in Rjukan (2023), Solidarity with political prisoners in Belarus at Sophus Bugges Hus in Oslo (2023), CIAHLITSY, an exhibition of queer art in Minsk and Brest (2019), and Halasy, exhibition of art de-stigmatizing people with mental health conditions (2019). The artist has also taken part in several art residencies and projects, the most recent being Solarpunk Campus Summer School in Rjukan (2023), I CONSENT Summer School at UKS in Oslo (2023), and R22: Repression – Expression // Violence – Creative Resistance at PRAKSIS in Oslo (2022).

Yanina Zaichanka (BY) is a Belarusian artist who is currently studying at the Oslo National Academy of the Arts. Prior to moving to Oslo, she had been actively involved in the contemporary art scene in Minsk. In 2018-2019, she studied Contemporary Art and Drama at the European College of Liberal Arts in Belarus. Her work has been shown at several solo exhibitions, including Untitled at the gallery Seilduken 2 in Oslo (2023), the Freedom (of Speech) from the Unbearable at Pradmova Festival of Intellectual Literature in Minsk (2020), and Being a Woman at ECLAB in Minsk (2019). Zaichanka has contributed to group shows, among others – Solarpunk Festival Exhibition at Kinogalleriet in Rjukan (2023), Solidarity with political prisoners in Belarus at Sophus Bugges Hus in Oslo (2023), CIAHLITSY, an exhibition of queer art in Minsk and Brest (2019), and Halasy, exhibition of art de-stigmatizing people with mental health conditions (2019). The artist has also taken part in several art residencies and projects, the most recent being Solarpunk Campus Summer School in Rjukan (2023), I CONSENT Summer School at UKS in Oslo (2023), and R22: Repression – Expression // Violence – Creative Resistance at PRAKSIS in Oslo (2022).

S.R. (NO)

S.R. (NO)

Maria Josef (DK/NO)

Maria Josef (DK/NO)

Helene Skuterud (NO) resides and works in Oslo. She is presently pursuing studies in material-based art at the Oslo National Academy of the Arts. Previously, Skuterud earned a bachelor’s degree in Three-Dimensional Design from the Birmingham Institute of Art and Design and a Master’s degree in Lighting Design from Sydney University. In recent years, she has served as a designer/maker for Lysrommet. Skuterud’s primary medium is sculpture and clay. She molds organic and abstract forms, ranging in size from handheld pieces to larger objects. These sculptures are either hand-built using coiling techniques or assembled from handcrafted and cast elements. Additionally, she delves into 3D technology, providing her with new avenues to explore form and materiality. Through incorporating technology into ceramic sculpture, she explores questions about identity, consciousness, and human experience in a world where technology holds an increasingly prominent role. Using clay, Skuterud strives to convey something about our surroundings and the bodies we inhabit. She seeks something familiar in the clay, aiming to engage the senses and consciousness through this material.

Helene Skuterud (NO) resides and works in Oslo. She is presently pursuing studies in material-based art at the Oslo National Academy of the Arts. Previously, Skuterud earned a bachelor’s degree in Three-Dimensional Design from the Birmingham Institute of Art and Design and a Master’s degree in Lighting Design from Sydney University. In recent years, she has served as a designer/maker for Lysrommet. Skuterud’s primary medium is sculpture and clay. She molds organic and abstract forms, ranging in size from handheld pieces to larger objects. These sculptures are either hand-built using coiling techniques or assembled from handcrafted and cast elements. Additionally, she delves into 3D technology, providing her with new avenues to explore form and materiality. Through incorporating technology into ceramic sculpture, she explores questions about identity, consciousness, and human experience in a world where technology holds an increasingly prominent role. Using clay, Skuterud strives to convey something about our surroundings and the bodies we inhabit. She seeks something familiar in the clay, aiming to engage the senses and consciousness through this material.

Amanda Kessaris (DK/US) is a multidisciplinary artist who uses her pieces as outlets to investigate gender roles, identity, and her experience of being a girl and woman within different cultures and generations. Kessaris works interdisciplinarily in a physical and digital reality to “reclaim” and portray traditional feminine symbols and materials as motifs in a contemporary context and as strong feminist symbols. Growing up around Hollywood’s “look at me” culture but very close to her Danish egalitarian-oriented family has created a form of identity crisis, which appears in her works. The concept of identity being something that can be taken on and off, as well as the eternal conflict between her multiple selves, act as reappearing themes throughout her practice.

Amanda Kessaris (DK/US) is a multidisciplinary artist who uses her pieces as outlets to investigate gender roles, identity, and her experience of being a girl and woman within different cultures and generations. Kessaris works interdisciplinarily in a physical and digital reality to “reclaim” and portray traditional feminine symbols and materials as motifs in a contemporary context and as strong feminist symbols. Growing up around Hollywood’s “look at me” culture but very close to her Danish egalitarian-oriented family has created a form of identity crisis, which appears in her works. The concept of identity being something that can be taken on and off, as well as the eternal conflict between her multiple selves, act as reappearing themes throughout her practice.

Adelina Allberg (SE) is an artist based in Trondheim, currently receiving a bachelor’s degree from the Trondheim Academy of Fine Art. Her work evolves around found objects and a rearrangement of them materially. This is done through highlighting certain characteristics or by twisting them in unexpected turns, and so in search for new identities. It is a play of material narration proceeding from the possibilities in the object itself, aiming to affect format as well as interpretation. Following an ecological stream of thought where the interconnectedness of entities is crucial, the studio practice is based on nonhuman interaction and co-creation. The works carry forward the, at times, irrational logic of insects, body structures of objects, and leftover material through subtle storytelling where categorization is of fluidity.

Adelina Allberg (SE) is an artist based in Trondheim, currently receiving a bachelor’s degree from the Trondheim Academy of Fine Art. Her work evolves around found objects and a rearrangement of them materially. This is done through highlighting certain characteristics or by twisting them in unexpected turns, and so in search for new identities. It is a play of material narration proceeding from the possibilities in the object itself, aiming to affect format as well as interpretation. Following an ecological stream of thought where the interconnectedness of entities is crucial, the studio practice is based on nonhuman interaction and co-creation. The works carry forward the, at times, irrational logic of insects, body structures of objects, and leftover material through subtle storytelling where categorization is of fluidity.