MIND TIME MACHINE AS A LIVING TECHNOLOGY.By Takashi Ikegami

Mind Time Machine as a Living Technology.

Any basic science can lead to innovative applications. Artificial life (alife) studies is no exception. The purpose of living technology is to bring to fruition the concepts developed through the study of artificial life, such as self-reproduction, autonomy, enaction, robustness, open-ended evolution, evolvability, and so on, in a real-world context (Ikegami, 2009).

By increasing our understanding of how we can connect artificial systems with natural environments, we can further our development of a theoretical framework that situates artificial life in an open environment. I discuss a principle for designing living technology in order to implement autonomy in technology. Obtaining robust autonomous behavior is a prerequisite for alife in the real world, but that doesn’t mean that alife ignores the environmental context, which is a mere independent behavior. However, alife must become sensitive to the environment, including human beings in the environment. Hence, the definition of autonomy here is the self-determining behavior of alife that utilizes past experiences and future predictions.

A mechanism of autonomous behavior may be attributed to a default mode (or a base-line activity) of a system while it receives no input from the outside. In human brain systems, a default mode network is proposed as a special neural activity that is responsible for the baseline activity of a brain without any specific task (Raichel et al. 2001). We generalize the notion of the default mode to any autonomous system. Living technology aims to help people to expand their experiences in everyday life; that is, it is a design for new affordances (i.e. that enable people to automatically connect to the environment in some new ways). Our hypothesis is that preparing a default mode is necessary for both perceiving and creating new affordances, even with artificial life.

Any basic science can lead to innovative applications. Artificial life (alife) studies is no exception. The purpose of living technology is to bring to fruition the concepts developed through the study of artificial life, such as self-reproduction, autonomy, enaction, robustness, open-ended evolution, evolvability, and so on, in a real-world context.

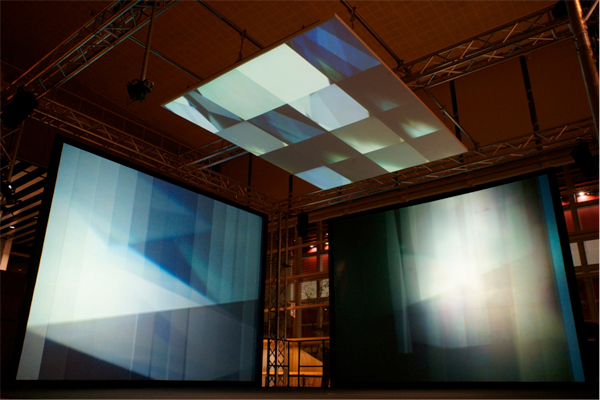

The example for this talk is about my previous art installation called Mind Time Machine (MTM) at Yamaguchi Center for Arts and Media in 2010. We built a machine (MTM) that runs continuously for ten hours per day and receives visual data from its environment using 15 video cameras. The MTM receives and edits the video inputs while it self-organizes the momentary now. Its base program is a neural network that includes chaos dynamics inside the system, and a meta-network that consists of video feedback systems. Using this system as the hardware and a “default mode network” as a conceptual framework, we would like to describe the system’s autonomous behavior in the above sense. Then, we will argue that the MTM can provide a testing ground for developing living technology.

In order to avoid confusing living technology with the classical AI (artificial Intelligence) approach, I compare the essentials of living technology and AI here. In general, AI is a symbol-based, fully-determined program that has an explicit goal to achieve. For example, general machine-learning techniques, including neural networks and evolutionary computation, are typical examples of the current AI approach to producing intelligence systems. On the other hand, living technology is an application of artificial life, i.e., autonomous embodied self-(re)producing systems. One key difference from the classical AI concept is that intelligence is only taken to be a side effect of life systems in artificial life studies. The primary purpose of living technology is not to optimize things but to sustain itself. The MTM uses neural networks and no explicit actuation. However, the MTM is not made to optimize things. Its objective is to survive in an open environment, without losing sensitivity to the environment. In this sense, the MTM is a proto-typical example of living technology. It also provides an example of a “meta-dynamical system” as its parameters and time step unit is not pre-defined.

Why do we need autonomy in technology? This is the question we must now ask. What is unique about the MTM is that it can reconfigure its memory structure by using autonomous dynamics, i.e., the video feedback and the neural dynamics, whose parameter is varied by storing the images. When this autonomous dynamic “dies,” it means that the dynamic becomes a fixed point and never changes by further accumulating the images. As we have seen in the previous sections, the MTM becomes quiet on rainy days or late in the evening.

We view this sustainable behavior with respect to falling down into the dead state as a “default mode” of the MTM. Like the default mode in a brain system, the default mode in the MTM is the baseline activity of the system. It self-sustains complex dynamics for maintaining, memorizing, retrieving, and reacting to environmental changes much as we expect the default mode of the brain system does. We expect that the default mode in MTM makes it possible to predict future environmental changes. This default mode characteristic might make it easier to let the MTM self-organize, rather than having us control it. That is why we need autonomy, even in artificial systems.

-Ikegami, T., Sustainable Autonomy and Designing Mind Time, ACM Digital Library (2010)

-Ikegami, T, A Design for Living Technology: Experiments with the Mind Time Machine, Artificial Life ( in press).

-Ikegami, T., Rehabilitating Biology as a Natural History, Adaptive Behavior, Aug 2009; vol. 17: pp. 325 – 328.

-Raichle, M. E.et al. Inaugural article: A default mode of brain function. Proc. National Academy of Sciences, pages 676-82, 2001.

Takashi Ikegami

The graduate School of Arts and Sciences,

University of Tokyo,

3-8-1 Komaba, Meguro-ku,

Tokyo 153-8902

English

English